by Terence Macquart (terence.macquart@bristol.ac.uk), Alberto Pirrera, and Paul Weaver

Wind energy is recognised as one of the greenest sources of energy, meaning that energy produced from wind turbines is generally less harmful to the environment than other energy sources, especially coal and gas. In other words, substituting fossil-based fuel with wind power is a great leap toward a more sustainable future. Although wind energy today only contributes a small fraction to the total energy consumed worldwide, considerable societal efforts are being made to build more turbines and wind farms to increase our wind energy capacity and hence produce cleaner energy. This is obvious in the UK, where the government aims to reach 50 MW of installed capacity by the end of 2030, quintupling its current wind energy capacity, a formidable aspiration.

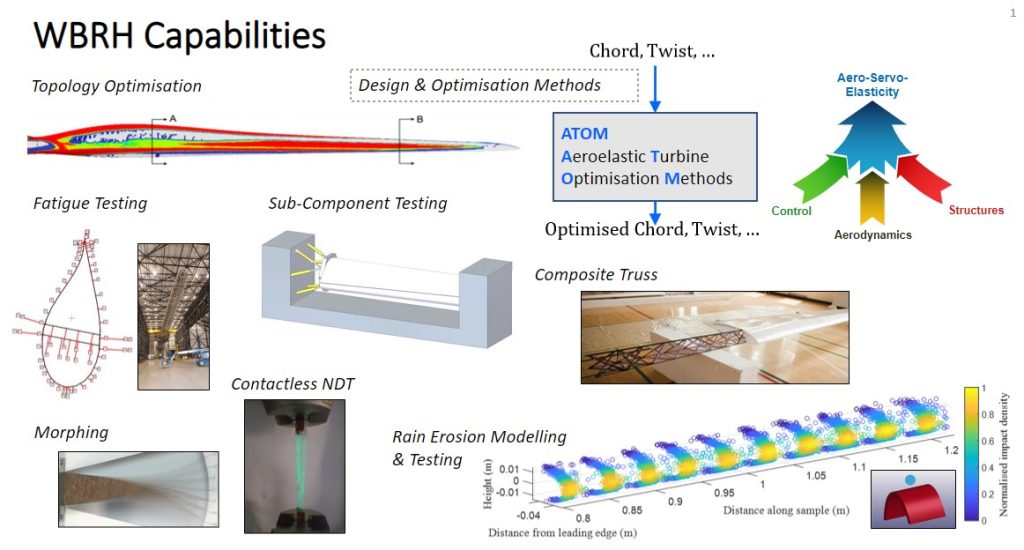

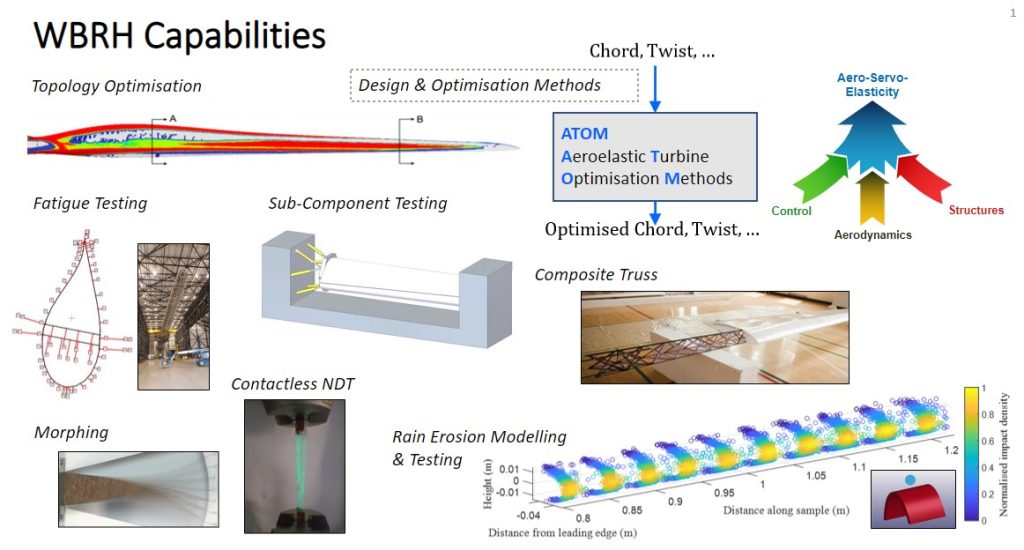

Modern wind turbine technology has rapidly evolved over the past decades to meet the rising demand for wind power. This can be seen by the gigantic size of modern turbines, dwarfing even the largest aircraft ever created. Such large and complex systems come with engineering and sustainability challenges of their own. The wind blade research hub (WBRH) is a collaboration between the University of Bristol and the Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult (OREC) that aims to address some of these challenges, as illustrated by the breadth of our work in the Figure below. Read more about each challenge addressed by researchers at the WBRH in the following paragraph.

Figure 1 : Overview of the wind blade research hub activities at the University of Bristol (REF: Mackie (2020) Establishing the optimal conditions for rotating arm erosion testing, materials characterisation and computational modelling of wind turbine blade rain erosion)

Improving wind turbine performance with holistic design tools:

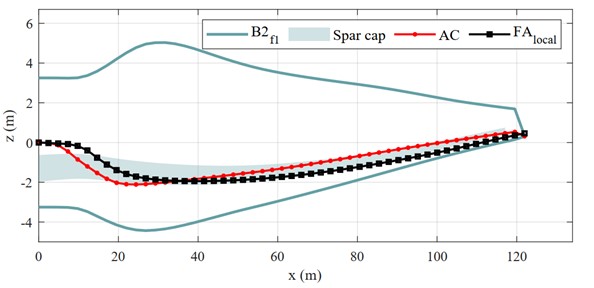

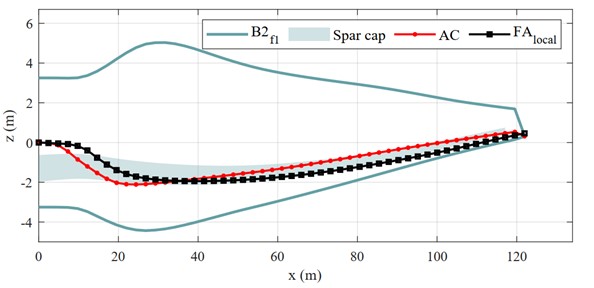

Although the design of wind turbines appears to be mature because we are repeatedly exposed to the familiar 3-bladed upwind turbine design, we know that their performance and sustainability could be further improved. However, wind turbines are also complex systems, and it is, therefore, very difficult, even sometimes impossible, to fully understand the impact that a change in design can have on the overall turbine performance. To overcome this challenge, our group has developed a sophisticated set of analysis and design tools which can navigate the complex design space of wind turbines and helps us better understand the design trade-offs we can make to improve them, leading to non-conventional designs as shown in the figure below. Reducing weight, also called light weighting, is a prime example of how such tools can help the wind industry; that is, by achieving a better understanding of aerodynamic and inertial loads on blades we can design lighter and more efficient blades, resulting in less raw materials being needed and more energy generated over the turbine lifespan. If you are interested in reading more on this topic, see the work of Dr. Samuel Scott (https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/312520978/Thesis_SamScott_Final.pdf).

Figure 2: Non-conventional design planform of a 15MW wind turbine blade, outperforming conventional designs. AC: Aerodynamic Centre, FA: Flexural Axis

Wind Turbine End-of-Life:

by Ian Hamerton & Terence Macquart

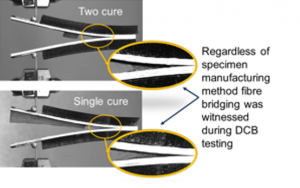

Large wind turbine blades require very strong material such as carbon fibre reinforced polymers which cannot currently be recycled effectively at large scales. As a result, at their end-of-life blades often go to landfills or are incinerated. In such cases, the costly carbon fibres making up the blade are lost, and new virgin material must be made. However, manufacturing virgin carbon fibres requires manufacturing process that are energy demanding and emit a lot of greenhouse gases. By contrast, materials that can be recycled, such as the steel making up the wind turbine tower, typically requires less energy to be made re-usable and emit less greenhouse gases (e.g. recycling steel reduces greenhouse gases emission by about 70-80%). The WBRH has two strands of research aiming to reduce the carbon footprint of wind turbines. The first one aims to rethink the design of modern turbines, using comprehensive design tools and life cycle analysis methods, to create new designs that can be made of more sustainable material. The second research strand investigates scalable ways in which we can recycle carbon fibres into new structural components, hence diminishing the overall environmental impact of wind turbine blades (Ian, Hyperdif, Lineat).

Leading Edge Erosion:

by Imad Ouachan and Robbie Heering

Leading edge erosion has developed into a significant issue for the wind industry. Raindrops, hailstones, and other particles impacting the leading edges of the blades cause material to be removed. This leaves a roughened blade surface, which degrades the aerodynamic performance of the blade, and hence its power production. The problem appears to be accelerated offshore due to high blade tip speeds and harsher operation environments. Viscoelastic Leading Edge Protection (LEP) systems are applied to the leading edge of blade to mitigate the onset of erosion. However, there is currently no LEP that lasts the lifetime of the turbine and regular repair is required. It is estimated that the issue costs £1.3m per turbine over its lifetime [X]. To support the development of improved LEP systems, the WBRH has worked with industrial LEP companies to investigate two key areas: (i) an understanding of the viscoelasticity of LEP systems and (ii) mechanisms to test and predict LEP performance. On the former, the WBRH has developed bespoke techniques to understand the drivers of LEP erosion performance by expanding knowledge in strain and frequency dependent behaviour and measurement techniques, including dynamic mechanical thermal analysis, acoustic measurement, and nano indentation. On the latter, a prediction model to relate an LEP’s test performance to its in-situ performance has been developed. This included an exploration of current erosion testing mechanisms to enhance their ability to realistically evaluate performance and the first characterisation of a wind turbine’s erosion environment. Together these two pieces of research have developed significant understanding of the drivers of erosion and important material properties, providing the wind industry with tools to further develop LEP systems and combat the important challenge of leading edge erosion.

Modular blades:

by Alex Moss

The overall aim of this work is to enable faster, cheaper, and easier production of wind turbine blades, which will help to reduce global dependence on fossil fuels. This is achieved through additive manufacturing, which will be used to build the internal structure of the blade. Acting as the composite layup surface, this would replace the costly and energy intensive steel-backed composite moulds currently used. Introducing automation into production process could lead to the creation of an assembly line, helping to make the 3 blades per day required to hit 2030 wind energy targets. To design these novel blade structures, topology optimisation is used to find the lightest possible configuration, reducing material use and energy. The wider industry is beginning to use recyclable materials to cut down on landfill waste at the end of life. The printed material takes this one step further, using recycled chopped carbon and glass fibre inside a recyclable resin. The printed material also replaces the balsa wood cores, into which the resin leaks during infusion which is wasted material and makes the balsa unrecyclable.

Advanced numerical models:

by Sander Van den Broek

As blades increase in length, they become increasingly difficult to structurally model. Traditional approaches using shell elements cannot accurately model the torsional stiffness as failure modes that become more important at larger length scales. At the same time, solid elements found in commercial finite element software are limited to lower-order descriptions of displacement fields. Convergence using lower order solid elements would require an excessive number of elements, becoming computationally prohibitive. Ongoing work at the WBRH is to develop higher-order structural modelling techniques that can simulate the nonlinear stresses and evaluate the stability of large wind turbine blades.

by Valeska Ting

by Valeska Ting

by

by

Finite element analysis (FEA) was used to determine the design alterations required for comparable performance, followed by a cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment to ascertain the subsequent environmental impact of these alterations. The preliminary results show a significantly greater volume of material is required in a flax-fibre blade to match reserve factor and deflection requirements; however, these models do show reduced environmental impact compared with the glass-fibre composite blades. End-of-life options assessed include landfill and incineration, with and wit

Finite element analysis (FEA) was used to determine the design alterations required for comparable performance, followed by a cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment to ascertain the subsequent environmental impact of these alterations. The preliminary results show a significantly greater volume of material is required in a flax-fibre blade to match reserve factor and deflection requirements; however, these models do show reduced environmental impact compared with the glass-fibre composite blades. End-of-life options assessed include landfill and incineration, with and wit

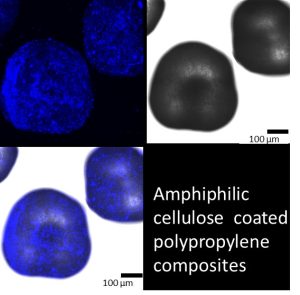

by Amaka Onyianta a.j.onyianta@bristol.ac.uk; Steve Eichhorn s.j.eichhorn@bristol.ac.uk

by Amaka Onyianta a.j.onyianta@bristol.ac.uk; Steve Eichhorn s.j.eichhorn@bristol.ac.uk