by Valeska Ting v.ting@bristol.ac.uk; James Griffith james.griffith@bristol.ac.uk; Charlie Brewster c.d.brewster@bristol.ac.uk; Lui Terry lt7006@bristol.ac.uk

by Valeska Ting v.ting@bristol.ac.uk; James Griffith james.griffith@bristol.ac.uk; Charlie Brewster c.d.brewster@bristol.ac.uk; Lui Terry lt7006@bristol.ac.uk

Of all of the modes of transportation that we need to decarbonize, air travel is perhaps the most challenging. In contrast to road or marine transport, which can realistically be delivered with battery or hybrid technologies, the sheer weight of even the best available batteries makes long-haul air travel (such as is needed to maintain our current levels of international mobility) prohibitive. Hydrogen is an extremely light, yet supremely energy-dense energy vector. It contains three times more energy per kilogram than jet fuel, which is why hydrogen is traditionally used as rocket fuel.

Companies like Airbus are currently developing commercial zero-emission aircraft powered by hydrogen. A key challenge for the use of hydrogen is that it is a gas at room temperature, requiring use of very low temperatures and specialist infrastructure to allow its storage in a more convenient liquid form. To deliver this disruptive technology Airbus are undertaking a radical redesign of their future fleet to enable the use of liquid hydrogen fuel tanks[5].

In its liquid form, hydrogen needs to be stored at –253oC. At these temperatures, traditional polymer matrices are susceptible to microcracking due to the build-up of thermally induced residual stresses. Research at the Bristol Composites Institute at the University of Bristol is looking at how we can develop new materials to produce tough, microcrack resistant matrices for lightweight composite liquid hydrogen storage tanks.

We are also looking at the use of smart composites involving nanoporous materials – materials that behave like molecular sponges to spontaneously adsorb and store hydrogen at high densities– for onboard hydrogen storage for future aircraft designs. Hydrogen adheres to the surface of these materials; more surface area equals more hydrogen. One gram of our materials has more surface area than 5 tennis courts, with microscopic pores less than 1 billionth of a meter in diameter. These properties allow us to store hydrogen at densities hundreds of times greater than bulk hydrogen under the same conditions. Whilst simultaneously improving the conditions currently needed for onboard hydrogen storage. Our research looks to improve this by tailoring the composition of these materials to store even greater quantities of hydrogen beyond the densities dictated by surface area.

With hydrogen quickly becoming recognised around the world as the aviation fuel of the future, France and Germany are investing billions in ambitious plans for hydrogen-powered passenger aircraft. To keep pace with the development of new aircraft by industry, there is a parallel need for rapid investment into refuelling infrastructure at international airports to allow storage and delivery of the liquid hydrogen fuel. Urgent investment to also upgrade the hydrogen supply chain is imperative. The UK Government’s announcement of new investment in wind turbines and offshore renewables will certainly boost the UK’s ability to generate sustainable hydrogen fuel and presents additional opportunities for new industries and markets.

It seems industry is finally ready to take the leap away from its reliance on fossil fuel to more sustainable technologies. Decisive action and public investment into upgrading our hydrogen infrastructure will allow us to realise the many benefits of this and will make sure the UK remains competitive in this low-carbon future.

Images and permissions available from:

https://www.airbus.com/search.image.html?q=&lang=en&newsroom=true#searchresult-image-all-22

by

by

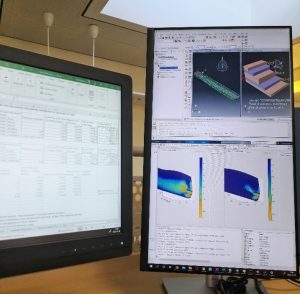

Finite element analysis (FEA) was used to determine the design alterations required for comparable performance, followed by a cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment to ascertain the subsequent environmental impact of these alterations. The preliminary results show a significantly greater volume of material is required in a flax-fibre blade to match reserve factor and deflection requirements; however, these models do show reduced environmental impact compared with the glass-fibre composite blades. End-of-life options assessed include landfill and incineration, with and wit

Finite element analysis (FEA) was used to determine the design alterations required for comparable performance, followed by a cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment to ascertain the subsequent environmental impact of these alterations. The preliminary results show a significantly greater volume of material is required in a flax-fibre blade to match reserve factor and deflection requirements; however, these models do show reduced environmental impact compared with the glass-fibre composite blades. End-of-life options assessed include landfill and incineration, with and wit

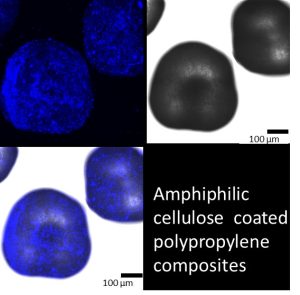

by Amaka Onyianta a.j.onyianta@bristol.ac.uk; Steve Eichhorn s.j.eichhorn@bristol.ac.uk

by Amaka Onyianta a.j.onyianta@bristol.ac.uk; Steve Eichhorn s.j.eichhorn@bristol.ac.uk